On April 1, 2021, I interviewed Daulton O’Neil at EarthX to introduce their forthcoming feature film, "American Forest Fires." This series consists of four parts, each lasting forty-five minutes, and analyzes the catastrophic fires that have been dominating the landscapes of our western states today and over the past 30+ years.

To view the four-part series, go to https://vimeo.com/showcase/10747980

Password: EarthxTV2023AFF

Aired: Thursday, April 1, 2021

Interview with Daulton O’Neil, formerly EarthX, and Amos S. Eno, President of LandCAN

For a video recording of the interview, feel free to watch it here.

Daulton: Western Forest Fires is our focus. What are we dealing with here?

Amos: First, we are staring at a century of conscious policies creating an incendiary environment, such as the suppression of fire in our western forests. This dates back to Teddy Roosevelt and Gifford Pinchot, what you might call the “Smokey the Bear” syndrome. It also includes the creeping effect of unconscious policies such as building homes for five decades in the wildland /urban interface and the effects of years of compounding environmental regulations.

Second, we are confronting the legacy of 50 years of environmental activism that designated millions of acres of Wilderness areas, precluding all forest management- “untrammeled by the hand of man” in ecosystems that Amerindians burned for millennia. With the addition of roadless areas and the huge regulatory imprint of endangered species listings, such as the 1990 spotted owl listing, which sounded the death knell for most small western forest products companies with the loss of 70,000 jobs in Pacific Northwest states.

Third, on top of those regulatory burdens, you have the annual litigation challenges by the environmental community to prevent tree salvage and forest management using the ESA, NEPA, and California clean air regulations. This trifecta of environmental off-limit litigation designations and oppositions to forest ecosystem health leads to the complete immobilization of forest management and the institutionalization of the philosophy that “You can’t cut a tree down.” This issue is not only occurring in the West; the same attitude of denial of forest management is imperiling the Pinelands of NJ. Here, a catastrophic fire could smoke out both Philadelphia and NYC due to the buildup of fuels over the last 50 years in a forest that abuts our largest swath of suburbia.

Daulton: What is the magnitude of the problem we are facing?

Amos: The problem is huge and will take decades to work out remedially. About half of the nation’s 885 million acres of forestlands require restorative forest management. In terms of western forest fires, the ten-year average is 61,000 fires per year, and 6.7 million acres burned annually. Last year, 2020, we experienced 57,000 fires in the West, which burned 10.4 million acres. We had comparable fire years in 2018, 2015-2017, 2011-2012, 2004-2009, and 2000-2001. Recognize that the smoke emanating from these fires is a major health threat and killer, causing 15,000-44,000 deaths. Over 300 western counties in the West are seeing major smoke waves in the current and next few decades.

Daulton: What about global warming, which environmentalists say is the cause of these fires?

Amos: That is the favorite ploy of the environmental community; it is what I call “agenda annexation”-apply any natural disaster to your favorite cause as a propellant for fundraising. Yes, we have a longer fire season, and yes, the West has experienced intermittent drought for several decades, but the cause of these fires is multi-decadal growth in fuel loads. California has more than 90 million dead trees in its forests. To put out these fires, we have to manage the forest on a continental scale.

Daulton: How do we get out of this mess; what are the solutions?

Amos: The solutions are actually pretty simple in terms of policy, but they will be expensive.

First, we need to take our cues from the Amerindian communities and their spokespeople, which is why our EARTHX show begins with Amerindian interviews. We have a plethora of anthropological data going back millennia and from our Amerindian antecedent’s cultural history doing extensive burning for forest management across North America. This is what our 21st century foresters now call “Pre-scribed burning”. In addition, in today’s forest management world, many tribes, like the Menominee in Wisconsin, are among the best forest managers in the U.S.

Second, the issue will only be addressed by sustained federal funding on the order of an additional $2 billion a year for the US Forest Service and companion federal agencies (BLM). We are currently spending a mere $510 million on forest management, and this needs to be initially quadrupled to $2-3 billion annually, with further ramped-up funding in out years for a 10 to 20-year and possibly longer duration to provide for sustained forest management on public lands. Everybody in Congress knows this issue, but for twenty years, Congress has not seen fit to do other than tweaks at the wheel of funding. This western forest fire issue should be incorporated as a major provision of any major infrastructure bill crafted by Congress in the next two years. This problem has been building for 100 years; the workout will take at least 30 years and an investment of billions $ per year- a trifling for current Congressional leadership.

Third, for a landscape-scale forest management implementation strategy, an unprecedented level of cooperation and formal coordination between multiple federal agencies (USFS, BLM, NPS as a core), state fire agencies (such as CAL Fire), local county governments, and private forest owners (NAFO) is needed.

Finally, the administration and Congress need to stop environmental litigants from attempting to impede aggressive forest management practices by passing no injunction legislation. Congress did this before in the face of national emergencies with labor with the passage of the Norris /LaGuardia Act in 1932.

Daulton: How should we address the fire future?

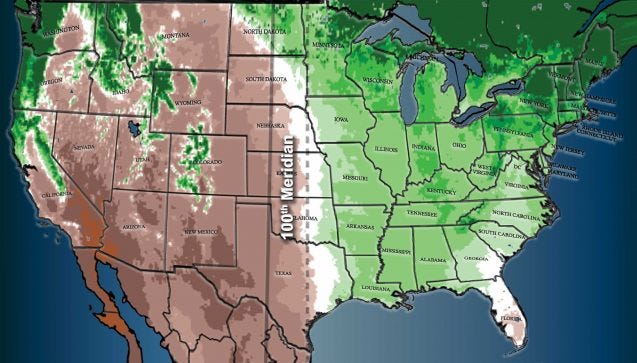

Amos: For more than 50 years, an East /West bicoastal elite has propelled the environmental movement in the U.S. The movement’s prescriptions, emanating from this bicoastal axis, are unrealistic and serve to undermine both the economy and American leadership and social strength. The environmental movement is destroying our western forests, which TR Roosevelt and Gifford Pinchot created as the foundational landscape for conservation west of the 100th meridian.

Map illustrating the U.S. 100th meridian.

The environmental movement flourished in the late 1960s as an enlightened, progressive force. Since the mid-1980s, it has degenerated into a regressive movement whose dominant principles are greed and veniality. For decades, environmentalists have been treading water intellectually and politically. At the turn of the century, global warming, a Western world charade for financial redistribution, revived their strengths.

We need to return to the credos of Pinchot and Roosevelt. Pinchot wrote in his book The Fight for Conservation (p.79), “The central thing for which Conservation stands is to make this country the best possible place to live in, both for us and for our descendants. It stands against the waste of the natural resources which cannot be renewed, such as coal and iron; it stands for the perpetuation of the resources which can be renewed, such as the food-producing soils and the forests; and most of all, it stands for an equal opportunity for every American citizen to get his fair share of benefit from these resources, both now and hereafter.”

A little more about the Author, Amos S. Eno…

Dive into the fascinating journey of Amos S. Eno, the visionary president and founder of the Land Conservation Assistance Network (LandCAN). For over 40 years, Amos has been a dynamic force in transforming environmental policy, challenging traditional thinking across government, corporate, and environmental sectors.

Amos's passion for the natural world was kindled on Mount Desert Island, Maine, and his New Jersey home. As a child, he explored the waters of Frenchman and Blue Hill Bays, hiked through Acadia National Park, and collected nature's treasures. His love for birdwatching remains so sharp that he can identify most perching birds even while traveling at 85 mph.

With a history degree from Princeton University, Amos's adventures took him to Nepal's Chitwan Park, where he conducted bird and tiger surveys and penned the first proposal for what is now Langtang National Park. His work in East Africa focused on integrating local communities like the Maasai into conservation efforts. After his time at the Department of the Interior, he earned an M.A. in natural resources from Cornell University.

Since founding LandCAN in 2000, Amos has developed a comprehensive suite of online tools to empower private landowners in sustainable land stewardship. His groundbreaking work includes leading the New England Forestry Foundation as executive director, where he orchestrated the two largest private land conservation easements in U.S. history, totaling 1.1 million acres.

Amos's impressive career also includes a decade as executive director of the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, where he regionalized operations for enhanced service. His roles at the National Audubon Society and the Department of the Interior further underscore his deep commitment to conservation.

Join Amos on his Substack page to explore his insightful writings and join the conversation on innovative environmental policies and conservation strategies. Follow his journey and be part of the change: Amos S. Eno's Substack.

If you'd like to contact Amos, you can reach him directly through Substack or via email at aeno@landcan.org. If you are interested in the Land Conservation Assistance Network (LandCAN), a 501(c)(3) non-profit, we invite you to explore www.landcan.org. LandCAN offers invaluable tools and resources for landowners, including searchable databases for conservation programs and access to over 57,000 experts and organizations nationwide. Our goal is to connect people to conservation by providing free access to critical information, tools, and services for the entire conservation community.